A long & winding road:

The story of circus

in Australia

BY MARK ST LEON

The circus was once one of Australia’s most popular forms of entertainment. Then came cinema, then television, and the circus all but died, in standard as well as strength, not to mention public esteem. Then some people began to re-think the idea of circus. It was not so much that circus was an inferior form of entertainment, it was just that it had been let down by economics and its apparent inability to accommodate changing social values. Judging by the growing storm of circus activity taking place around Australia today – countless circus groups, a federally-funded national circus school and regular imports and exports of circus activity in one form or another – circus is finding a new meaning and relevance. Circus in Australia lives and, from all appearances, has an exciting future. It also has a rich past.

In colonial and early 20th-century Australia, the travelling show was the practical solution to a fundamental economic problem: how to provide a small and widely-distributed population with access to popular entertainment. From the early 1850s, travelling entertainers delivered to Australians an extraordinary diversity of culture – popular, high and low – such as: opera, minstrel, photographic, magic, bellringing, gospel singing, boxing, menagerie and carnival, to name a few. However, the earliest demonstrable example of an Australian travelling show, and the most enduring, was the circus. The colonial popularity of horses and horsemanship, wrote Richard Twopeny in 1883, accounted for ‘perhaps the most critical and appreciative circus audiences in the world’.

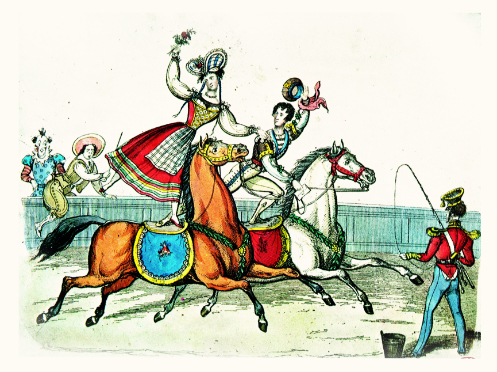

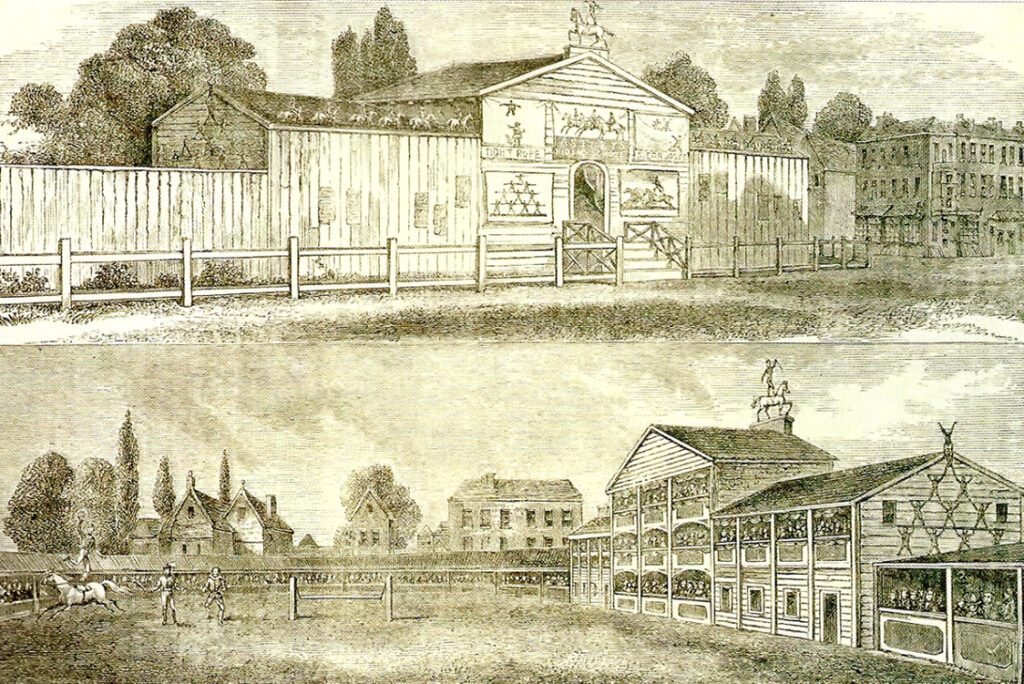

The modern circus crystallised in London from 1768. Open-air displays of trick horsemanship given in a field called Ha’penny Hatch on London’s southern outskirts began to assume the form that we today associate with the circus. Crucial to these developments was a former cavalryman and veteran of the Seven Years War, Sergeant-Major Philip Astley. Astley (d.1814) combined displays of horsemanship with those of clowns, ropewalkers and gymnasts. By 1779, he had enclosed these displays within a permanent venue, near the south side of Westminster Bridge, which he named Astley’s Amphitheatre. This new genre of entertainment was popularly known around London as ‘the circus’ and the name stuck. While the Roman circus and the circus of modern times do share some features, the term ‘circus’ was 18th century London vernacular to describe the large, open-air, circular riding tracks used by recreational riders, traces of which remain today in thoroughfares such as Piccadilly Circus.

Although destroyed by fire several times and rebuilt, Astley’s Amphitheatre remained a major international venue for circus long after its founder’s death. The establishment reached the peak of its fame in the years 1825-41 under the management of the superlative horseman, Andrew Ducrow (1798-1842). Ducrow raised the spectacle of circus riding to an art form. His exquisite equestrian-based pantomimes and spectacles were imitated in circuses throughout the British Isles, on the Continent, in the new United States and in the new colonies of Australia.

The concept of the modern circus was still a new genre of entertainment when The First Fleet sailed in 1788. Indeed, we may speculate that many of the Fleet’s human cargo had witnessed, or were at least aware of, the delights of Astley’s. But organised popular entertainments were not among the priorities of a penal settlement. Sydney and Hobart Town were not served by regular theatre performances until the 1830s and then only with difficulty. The ropewalkers, gymnasts and equestrians who made occasional appearances as early as 1833 proved transient. Some 60 years passed after the arrival of the First Fleet before the elements necessary to launch a colonial circus industry – bureaucratic largesse, entrepreneurs, performers, audiences and prosperity – fell into place. Of the few settlements along Australia’s coastline, Launceston held the least promise as the foundation place of Australian circus. In 1847, this minor seaport held a population of only some 10 000, most of whom served the town’s penal purpose in some or another. Nevertheless, the location gave birth to the first comprehensive and successful demonstrations of colonial circus activity and, with it, the launch of a colonial circus industry.

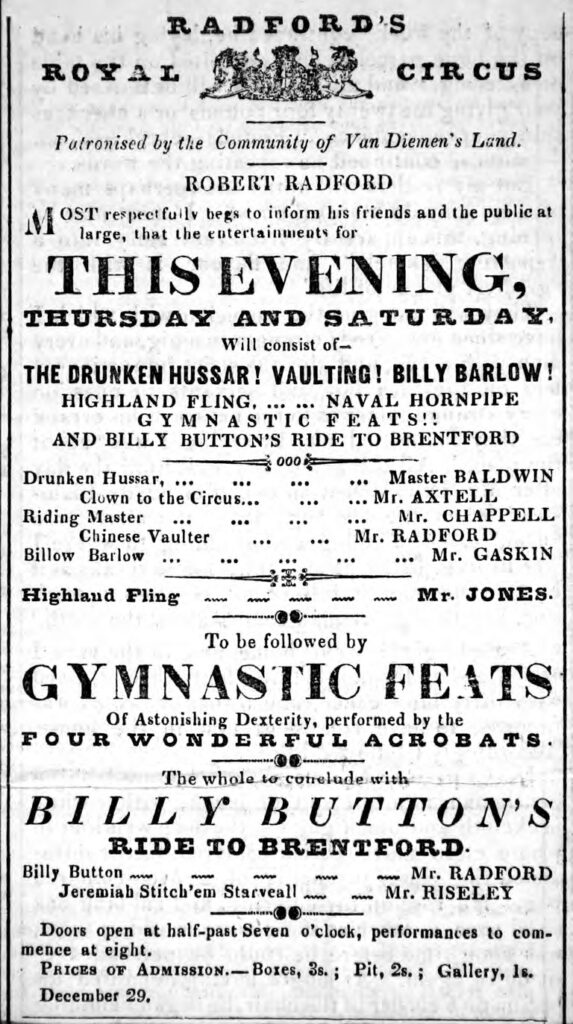

There, in 1847, a Devonshire-born equestrian, horse dealer and publican named Robert Avis Radford (1814-65) pioneered the first successful circus in Australia and, with it, a continuous Australian circus tradition. This Astley’s ‘on a limited scale’ was a building of simple construction – presumably timber, iron and canvas – located in the yard of Radford’s Horse & Jockey Inn in York Street. It opened on the evening of Monday, 27 December 1847. With a little company of performers, some of whom were former convicts, Radford presented feats of horsemanship, dancing, vaulting, gymnastics, acrobatics, clowning and equestrian burlesque. The features of Astley’s Amphitheatre and the equestrian art of Andrew Ducrow were thus transposed, on a miniature and probably rougher scale, to this most distant point on the globe.

Following Radford’s example, colonial circus exhibitions were soon given in amphitheatres of modest descriptions in Port Phillip, Maitland, Singleton, Sydney and Adelaide in the years leading up to the first gold rushes. From these early establishments were derived the travelling circus troupes that traversed the eastern colonies to deliver equestrian, acrobatic, tumbling, clowning and tightrope performances to audiences in city, town and bush

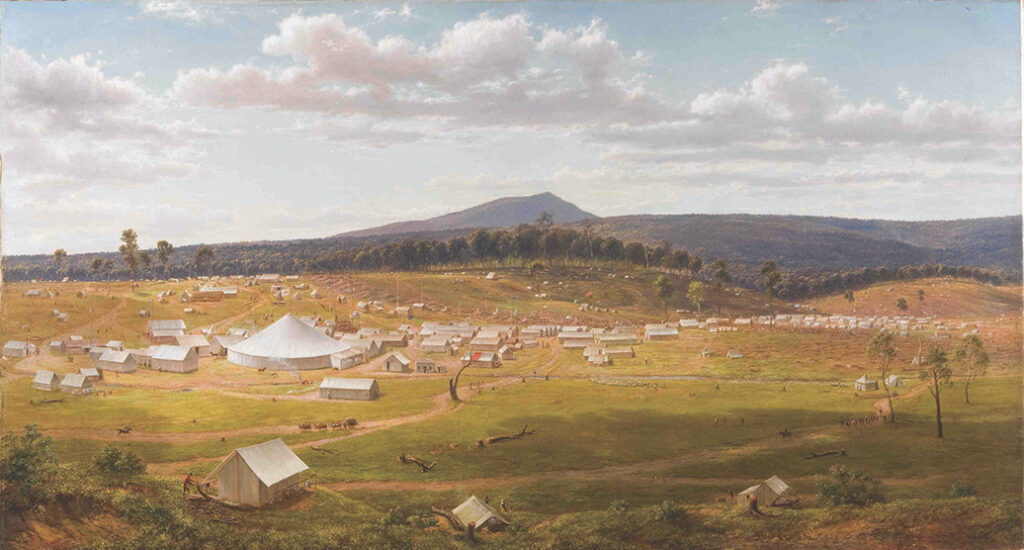

From Sydney in February 1851, Henry Burton, a professional English circus man, took to the road with Australia’s first peripatetic company. Reaching Maitland, the discovery of gold on the Turon soon deprived him of an audience. He and his troupe then followed, with packhorses, an ill-formed road via Mudgee to reach the diggers on the new goldfield. For a time, the gold of the diggers focussed and sustained colonial circus activity at places such as Sofala and Ballarat. Golding [known professionally as ‘James Henry’] Ashton (1820-89), who gave his first Australian appearances as ‘the renowned British horseman’ in Radford’s in 1848 and opened his own amphitheatre in 1851, was travelling the New England goldfields with his tented circus by the summer of 1852-53. Ashton’s descendants remain active in Australian circus today and conduct, arguably, the oldest circus companies in the English-speaking world.

Another of Radford’s performers, the London-born acrobat, equestrian and ropewalker John Jones (c.1826-1903) was a witness to the events leading up to the Eureka Stockade at Ballarat at 1854. Indeed, the bandsmen of Jones’ Circus were commanded at gunpoint to serenade the diggers as they worked to construct the stockade. Jones later (1865) adopted the professional -and less prosaic- nom d’arena of St Leon.

From the late 1870s until the early 1920s, St Leon’s was one of Australia’s major circus companies and, by the early 1900s, the family was well-represented in American circus as well.

After 1854, the circus routes began to extend beyond the familiar precincts of the eastern settlements and the interior goldfields. The early circus proprietors found, as had the wandering minstrels of medieval Europe and the circus men of the American frontier, that it was easier to change audience than repertoire. To change audience, they had to change location. Moving beyond the confines of the amphitheatres, the Australian circus acquired the characteristics of mobility with which it is today identified – tents, touring and transportability. Light, flexible tents replaced the early cumbersome structures called booths that had to be erected, dismantled and transported between each location visited.

Tented circuses reached Moreton Bay [now Brisbane] in 1855 and Adelaide in 1856. It took longer for the circus to reach Fremantle (1869), Cooktown (1889) and Darwin (1914). Not until the 1890s, in the wake of the fabulous gold rushes, did the larger circus companies of Australia’s eastern seaboard regularly visit Western Australia. Advance agents travelled ahead to advertise the circus along its route. A theatrical licence, usually costing a guinea and good for 12 months, was required in each colony visited.

There was something peculiarly appropriate about the circus in an Australian context. On outward appearances, the circus reflected some of the most pervasive features of Australian life: on the one hand, it eschewed matters of intellect; on the other, it reflected our pursuit of athletic glory in any form and irreverence for pretentiousness and authority. But the worst of circus also concealed objectionable practises such as the ‘adoption’ of young children – often illegitimate or abandoned – into indescribably harsh apprenticehips as circus performers.

In many respects, Australia’s itinerant circus people of the late 19th and early 20th century were explorers who constantly pushed at the frontiers of human settlement and faced the natural challenges of drought, fire and flood; and the lack of roads, bridges and communications that we today take for granted. The smaller circuses went to extraordinary lengths to reach people in the most remote areas of the bush and well away from the beaten track, the shearers, miners and the railway construction gangs. Early circus proprietors did their best to identify with these people of the bush by generously supporting appeals for hospitals, schools, churches, orphanages, Masonic halls or other buildings of civic importance in the towns they visited. Even the bushrangers tended to take a kinder view of a circus on the road preferring to wave it through rather than bail it up.

The circus was also a highly popular entertainment throughout the United States. The first circuses reached California in 1849 and within a few years one circus troupe, J A Rowe’s North American, had crossed the Pacific to Melbourne where Rowe erected a ‘commodious’ pavilion and played in the gold-stricken city for two years. After the interruption of the Civil War (1861-65), the completion of the transcontinental railway (1869) and the regularisation of trans-Pacific shipping services (1873), the ‘fabled land’ of Australia once again claimed the imagination of American circus men. Between 1873 and 1892, a steady stream of American circus companies, including the largest, visited Australia. The development of colonial rail systems facilitated their tours. The parade of Cooper, Bailey & Co’s Great International Allied Shows – the lineal ancestor of the later Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey’s Combined Shows – through the streets of Melbourne, carnival style, aroused a sensation in 1877. Its caravans were gaudily painted and decorated with parables from the scriptures. This was the ‘great moral show’, the one patronised by the American clergy, the circus that did not show on a Sunday.

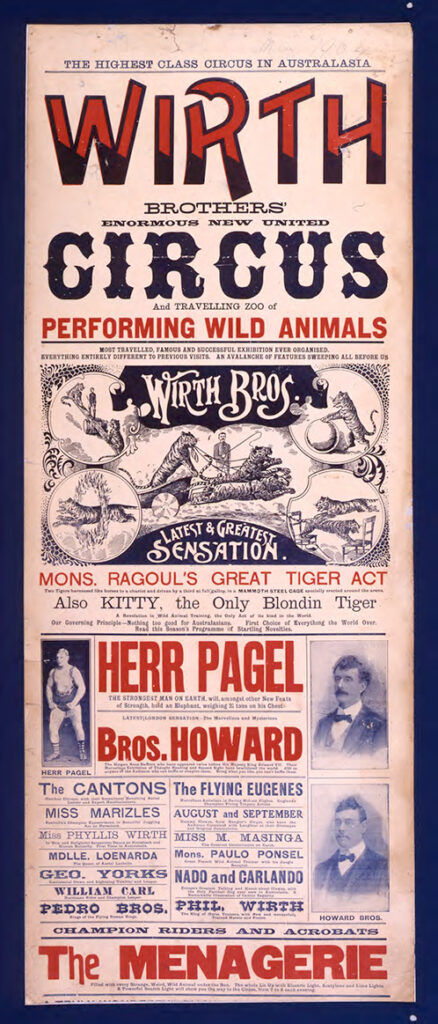

The largest Australian circuses did their best to emulate the American examples. Visiting Wollongong in 1883, St Leon’s Circus boasted ’150 men and horses’ – counted as one figure, such was the colonial esteem in which the quadruped was held – and a parade more than half-a-mile in length. By the close of the 19th century, FitzGerald Bros and Wirth Bros toured the six states of Australia and New Zealand by rail and steamer along standardised routes, with imported companies of artistes, menageries of wild animals, large bands of professional musicians and lavish promotion. In 1901, FitzGerald Bros Circus comprised 112 people and was conveyed on 34 rail carriages. After the co-incidental deaths of the FitzGerald brothers in 1906, continents apart from each other, Wirth Bros was left as Australia’s largest circus company, a position it held until its final closure in 1963.

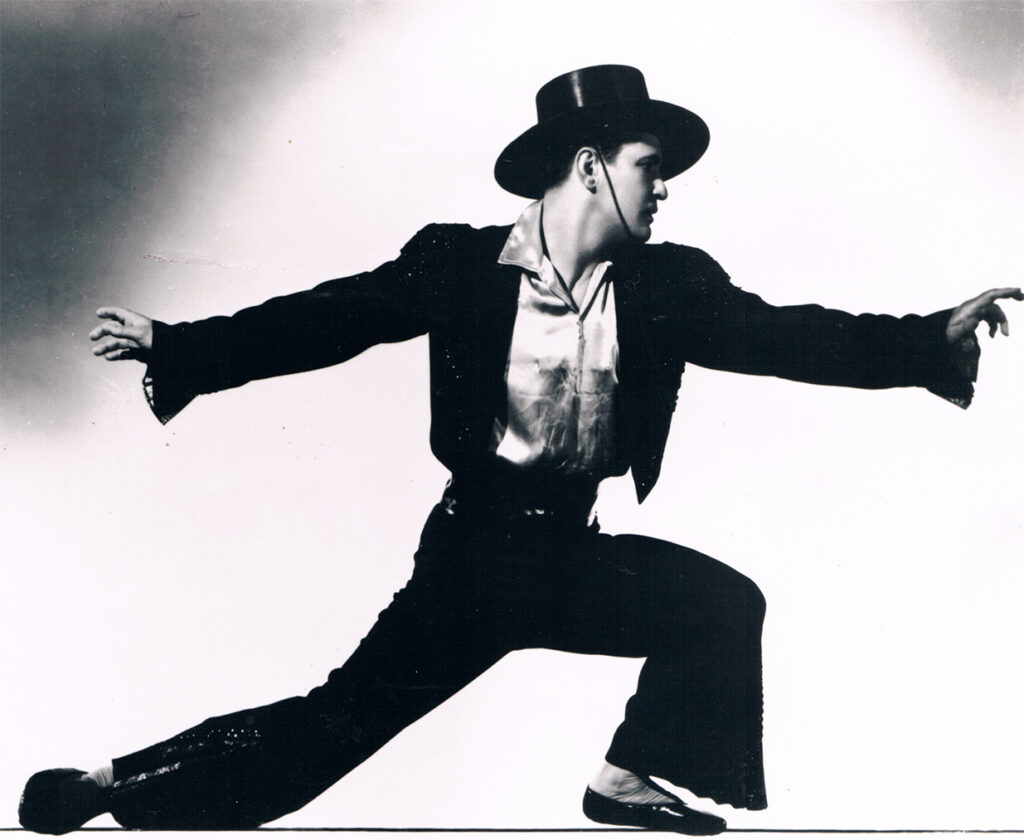

Australia nurtured some of the great stars of the international circus in this era. Two artists in particular deserve mention, although largely forgotten in their native land. These were the superlative equestrienne, Bundaberg-born May Wirth (born May Zinga, 1894-1978), an adopted daughter of the Wirth family; and the Indigenous tightwire dancer and acrobat, Narrabri-born Con Colleano (born Cornelius Sullivan, 1899-1973), whose family started out with its own circus from Lightning Ridge in 1910.

By the 1920s, Australian circus proprietors, long-accustomed to the free-spirited conduct of their business, were now faced with municipal restrictions governing parades and the posting of bills, while the cost of employing star acts and unionised musicians had soared. New forms of competition emerged in the form of the picture shows which reached the country districts from 1908, while cinemas were erected in the larger country towns from 1915. A motorised circus could move faster in this changing economic landscape. An advance agent travelled ahead of Ashton’s Circus in his own motor car in 1911 but motorisation did not become widespread in circus until the late 1920s and, as late as 1935, West Bros Circus crossed the Nullarbor Plain with horses and wagons. More than 20 motorised ‘road shows’ were active in the 1930s, such as Ashton’s, Bullen’s, Gill’s, Lennon’s and St Leon’s, while the largest, circuses, Wirth’s and Perry’s, were transported by rail.

In 1942, after war with Japan commenced, circus and other travelling show activity was severely curtailed. During World War I, circus horses had been commandeered by the army. Now, in World War II, the army requisitioned circus vehicles. As a morale-boosting measure, Wirth’s and Perry’s, were permitted to operate on a reduced scale for the remainder of the war.

After 1945, the circuses flowered once again, unfettered by wartime restrictions and able to ride upon the ever-increasing prosperity of post-war Australia. There were 17 circuses travelling the country by the mid-1950s. Then television was introduced. Wirth’s ceased operations in 1963 after 80 years of continuous travel and an international reputation to its name. The Wirth management placed blame for the demise on television although unpaid taxes, soaring rail costs and mismanagement contributed to the failure. The Bullen family, after more than 40 year’s touring throughout Australia and New Zealand, voluntarily pulled its 94-vehicle circus off the road in 1969 and re-directed its energies towards the establishment of wild animal safari parks.

By 1973, there were only four circuses of any consequence left to tour the continent: Ashton’s, Circus Royale, Sole Bros and Alberto’s, the last two conducted by descendants of the famous Perry family.

The public’s appetite for high quality circus entertainment was satisfied by the regular visits of the Great Moscow Circus and televised circus programs from Europe and America. But, despite the ascendancy of the electronic entertainment media, the ethos of an Australian circus tradition was not dead: it merely required updating.

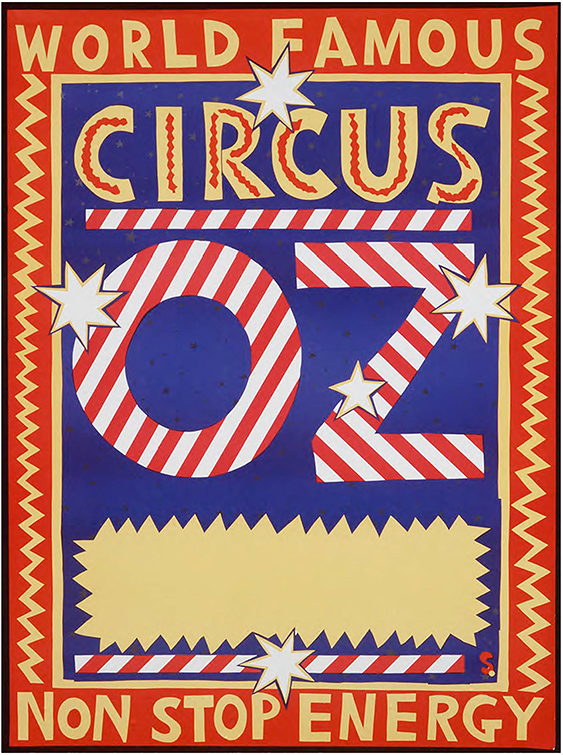

Broadly speaking, Australian circus is today divided between contemporary groups on the one hand, and the more conventional family-based itinerant companies on the other. Some of the latter have been active for well over one hundred years, their programs dependant to varying degrees upon the presentation of animals, whether domesticated, exotic or wild. The former can be divided between the avant-garde ‘new wave’ companies, which are constantly pushing the meaning of circus to (and even beyond) conventional limits, and the youth-focussed community circus groups which are flowering all over the country in various forms and guises. The jewel in the contemporary circus crown belongs firmly to avant-garde group Circus Oz, based in Melbourne. Launched in 1978, this company now ranks as one of Australia’s major performing arts organisations.