The St Leons:

A Family Circus Saga

BY MARK ST LEON

In the 1850s, travelling by horses and wagons, tented circuses began to move between the goldfields of New South Wales and Victoria. The itinerant circus replicated the family-based tradition brought from the Old World, England especially. Out of the early circus families were built names, reputations and dynasties in the show business aristocracy of the bush.

An English horsetrainer and publican, Robert Avis Radford deserves credit for opening Australia’s first ‘circus’ in Launceston in December 1847. It was actually a fixed location ‘amphitheatre’, a combination of circus ring and theatre stage. Radford and his troupe were well-received in their venue, a ‘humble imitation’ of London’s famous Astley’s Amphitheatre. On Radford’s opening night, a ‘Mr Jones’ was one of ‘four wonderful acrobats’ who performed ‘gymnastic feats of astonishing dexterity’. Although his prosaic name gave little promise of future celebrity, the appearance of ‘Mr Jones’ laid the foundations of the St Leon family, probably Australia’s earliest family of entertainers. When the last of the St Leon family retired from circus in the 1960s, five generations of the family had served the world of spangles and sawdust in both Australia and the United States – and had appeared in vaudeville, theatre and film.

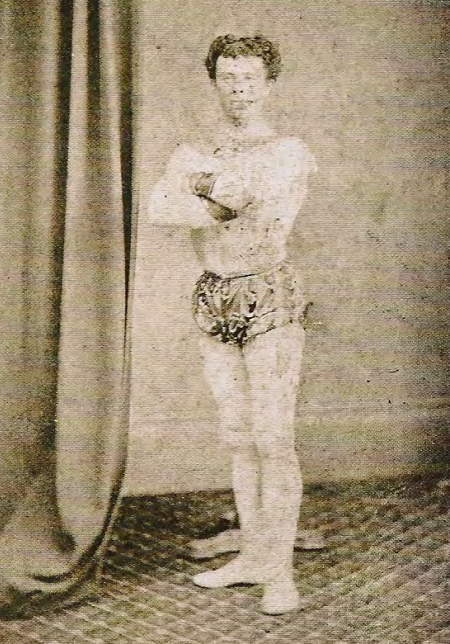

In London in 1842, John Jones, performed as a ‘tumbler’ in Astley’s Amphitheatre, but, when implicated in a petty theft, was transported to Van Diemen’s Land. Granted early freedom, he soon enlisted with Radford’s Royal Circus where he revived his acrobatic skills and learned equestrianism and tightrope walking from the expert performers around him. He also found the time to marry Margaret Monaghan, a 17-year-old Irish girl. Of their eight children, three sons, Gus (b.1851), Walter (b.1856) and Alfred (b.1859) began training for a life of acrobatics and horsemanship as soon as they were toddlers.

In 1850, John Jones brought his own equestrian troupe to Sydney. They opened at the Royal Australian Equestrian Circus in York Street. The circus proved a popular source of amusement in a city of some 30,000, opening three nights a week with programs of horsemanship, ropewalking, acrobatics, clowning, singing and pantomime.

In the winter of 1851, Jones and his troupe followed, with packhorses, an ill-formed road by way of Mudgee to reach the new goldfields at Sofala near Bathurst. His circus ‘tent’ was a mere enclosure of canvas sidewalls while the ‘lights’ consisted of burning paraffin-soaked rags placed in fish tins filled with mud and fat. Standing on a horse dressed in tights, Jones held a little barefooted Aboriginal boy outstretched in various artistic poses as the diggers threw coins into the ring to reward their pluck. Jones often had to purchase miners’ rights to a ground before he could put on his show but, in this way, he acquired considerable property.

After opening an amphitheatre in Geelong in 1853, Jones moved onto the Ballarat goldfields. Towards the end of 1854, the gold licencing issue reached its dramatic climax, and soldiers, troopers and police were already on the way from Melbourne. The diggers commandeered Jones’ circus tent to store their arms and ammunition. Around the circus itself, Jones and his men built their own barricades with bails of straw for protection in the coming affray. At gunpoint, the diggers forced the circus bandsmen to serenade their comrades as they laboured to build their doomed fortress, the Eureka Stockade.

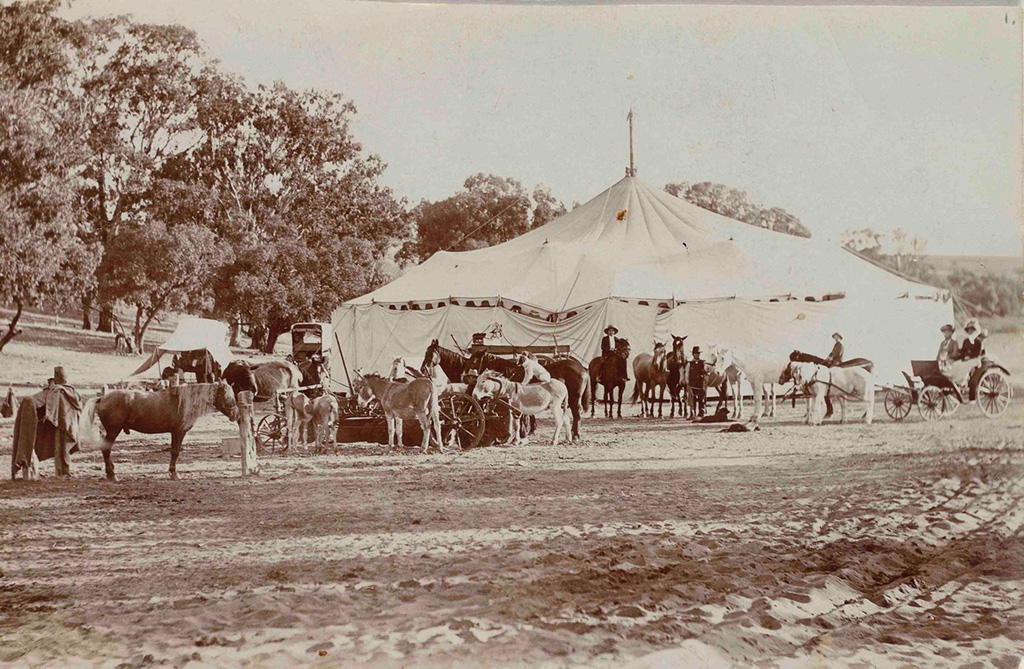

But the heady days of the Australian gold rushes were already coming to an end. The several circus troupes which had moved between the goldfields, Jones’ included, now began to move between the emerging regional settlements of south-eastern Australia, travelling with horses and wagons. In a land where formed roads were few and rivers unbridged, the circus people had to cut their own tracks through thick scrub, ford wide rivers and negotiate deep ravines. Owing to flooded creeks, Jones had to offload the ‘weightier portion’ of his circus behind in the bush before he could reach Wagga Wagga in the winter of 1859.

When the Confederate raider Shenandoah, called in to Port Philip early in 1865, officers and men were treated to an evening at Melbourne’s ‘high class’ Theatre Royal. They were entertained by a gymnastic troupe, ‘The Wonderful St Leon Family’ apparently from the ‘Gymnase Imperial’ in Paris, with their acrobatics, trapeze, dancing, comedy and singing. The more astute in the audience may have recognised what the visiting Confederates could not: this was the renowned colonial equestrian, John Jones, and his three young sons, Gus, Walter and Alfred. The young Gus performed ‘astounding feats’ 30 feet in the air on a trapeze slung from the roof of the theatre.

The substitution of an inherited prosaic family name with a romanticised, theatrical pseudonyms was a popular device for self-promotion and self-legitimation. First employed by 19th century performing artists, the device is still used by rock stars and movie idols today. The Theatre Royal’s manager, the famous English actor, Barry Sullivan probably suggested the ‘St Leon’ pseudonym to John Jones for his little troupe. The same pseudonym was already used by the famous French dancer, Arthur Michel (1821-70), the choreographer of the ballet Coppelia, with whose work Sullivan was probably familiar. In any case, the name stuck and, by the early 19th century, ‘St Leon’ had become the accepted family name.

After their 1865 Melbourne debut, The St Leon Troupe travelled south-eastern Australia for several years giving their ‘classical drawing room entertainments’, sometimes in assembly rooms and hotel saloons, sometimes in canvas sidewalls, but perfecting their performing skills as they went.

By the early 1870s, the three St Leon boys were skilled in all the arts of the circus, acrobatics and equestrianism especially. The family joined the premier colonial company, Burton’s, in time to participate in the Grand Hippodrome in Adelaide in 1873. In seven exciting races involving chariots, hurdle races and Roman riding, they defeated the riders of Bird & Taylor’s for the circus premiership of the colonies.

Outside Kilmore, in May 1875, father and three sons parted company from Burton’s Grand United Circus Company and started on the road as St Leon’s Royal Victoria Circus. Moving northwards into New South Wales, they built their circus as they went, engaging new performers and staff, buying more wagons and horses. By the 1880s, St Leon’s Circus was ‘a power in the land’, travelling far beyond the reach of the expanding railway systems and even reaching, by steamer, Cooktown and Normanton. The half-mile long cavalcade of ‘150 men and horses’ and a menagerie of wild animals, headed by a glittering band carriage, was a welcome relief to the isolation and monotony of outback life.

By 1885, the company had grown so large that it was divided in two and the brothers, Gus and Alf, toured their portion – St Leon’s Royal Palace Circus – through New Zealand with success. At Rotorua, not even the threat of a nearby active volcano could contain the people’s enthusiasm over a visiting circus. After 14 years continuous operation, the original family circus was reduced to insolvency in 1889. Although the family fortunes languished during the recessionary 1890s, they were by no means extinguished and the three St Leons sons produced the next generation of circus performers.

The ‘old man’ St Leon, as he was affectionately remembered, the former John Jones, died suddenly in Melbourne in 1903. Obituarists described him as the ‘oldest circus proprietor in the colonies’ and ‘one of the finest horsetrainers in the world’. As a mark of respect, the Wirth brothers, the sons of his former German bandsmen, and by then the proprietors of Australia’s largest circus, sent their band to play a requiem at his graveside. Already, the family had started to go separate ways.

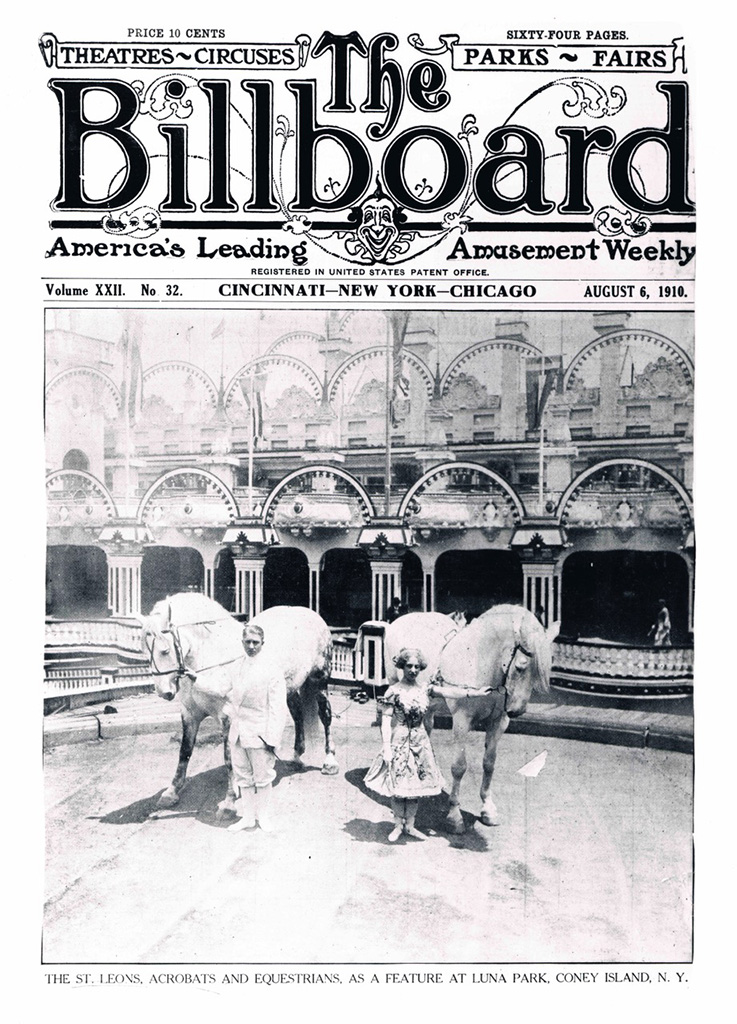

In 1899, Alfred St Leon and his family reached the United States and began to rise swiftly in American circusdom. In 1903, the Lubin Company of Philadelphia made a newsreel of their acrobatic work. Each summer, during the years 1908-13, Alfred’s children, Elsie and George, were a featured riding act at the outdoor circus at Luna Park, Coney Island, a popular pleasure resort and amusement park for New Yorkers. When not at Coney Island, the family performed the live, on-stage circus scenes in Polly of the Circus, a popular production toured throughout the United States and Canada. Alfred’s daughter, Ida, eventually graduated to the speaking role of ‘Polly’ and launched her theatrical career. In 1917, Ida was voted one of America’s ten most popular actresses.

Remaining in Australia, Walter St Leon and his family formed St Leon Bros Circus in 1904. Their last tour was by riverboat down the Darling River in 1912, playing at townships and shearing sheds along the way. Just above Wilcannia, the circus was ‘shipwrecked’ when the boat hit a snag and sank – in waters much deeper than they are today. In the 1920s, Walter’s son, Norman, presented a posing dog act in vaudeville and steered the fledgling Bullen Bros Circus to success in the 1950s. Another son, Clyde, ended up in the United States where he and his family performed a popular ‘teeterboard’ acrobatic act in circus and nightclubs in the 1950s.

In 1901, Gus St Leon and his family landed in the United States. After touring the United States with Ringling for two years, the family formed its own circus and travelled down into Mexico as El Circo Anglo-Americano. At Pahuca in 1904, Gus’s daughter, Daisy, married an American gymnast, Alf Honey and they brought forth a fourth generation of the family, to be known as The Honeys. Returning to the United States, Gus’s sons formed an acrobatic act for the vaudeville circuit, called The Five St Leons. They once shared a bill with black-faced singer, Al Jolson. By late 1908, the Gus St Leon family had returned to Australia and, at Liverpool, outside Sydney, formed Gus St Leon’s Great United Circus, the main circus to carry the St Leon name until the 1940s. The 16-piece circus band, supplied with the latest rags and marches from America, was the envy of even professional brass bands.

In 1926, the Honeys (Alfred, Daisy and seven children) returned to the United States and soon established a popular acrobatic act in vaudeville. Golda Honey charmed audiences with her work on the tightwire and a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith wrote a popular song in her honour, Stay as sweet as you are. The Honeys were instrumental in forming an American edition of St Leon’s Circus which toured New England and Canada in 1931 only to be beaten by the depression.

At home and without the Honeys, it was a smaller St Leon circus – chiefly Gus’s sons, Reg and Syl – that travelled regional Australia. The spread of country cinemas and the travelling vaudeville shows raised new forms of competition for the time-honoured circus. Not to stand in the way of progress, the family reluctantly swapped its horses and wagons for motor transport to negotiate the changing economic landscape. The 1930s were a struggle for a small family circus but, by 1939, it was reported that St Leon’s Circus was ‘still going strong’ in the country districts. A family riding act, The Riding St Leons, comprised of Reg St Leon’s three eldest children, the family’s fourth generation, was the centrepiece of the program. The circus closed up late in 1941 just as wartime restrictions – petrol, lighting, manpower and transport – began to severely restrict all travelling show activity.

The Riding St Leons maintained their act in trim during the war years. The troupe was a regular feature of the Wirth circus program into the early 1950s and expanded to four, then five riders as younger members of the family joined the troupe. The troupe was often billed as ‘Miss Peggy and Her Equestrians’ after its premier rider, Peggy St Leon (b.1920). There were plans to take the act to America but the Korean War made things uncertain and the troupe broke up in 1953. An attempt by Peggy’s brothers, Joe and Leo, to re-form the family circus in 1957 was short-lived. By this time, television had sounded the death-knell of the large circus. By the early 1960s, the last of the St Leon family had passed out of active circus life. In 1963, Australia’s largest circus, Wirth Bros, was forced into liquidation and Australia’s once vibrant circus industry descended into a long slumber, only re-awakened by the emergence of the new groups of the government-funded contemporary era such as Circus Oz and the Flying Fruit Fly Circus.