I recently spoke to The Goulburn Historical Society, here is Part 1 of my presentation:

As some of you may know, my field of personal interest is Australia’s circus history. In 1969, aged 17, I began to enquire into my own family’s rich but largely forgotten contribution to Australian circus, a contribution that extended over five generations, from 1847 until the 1960s.

As I groped my way through musty old newspapers and archival records, I gradually realised that I had stumbled upon an almost completely unexplored area of Australia’s history. Although my own family’s circus saga was the focus of my enquiries, I became fascinated by the entirety of the travelling show industry that that was the main source of live entertainment for most Australians until the arrival of the electronic media.

Before there was television, cinema or radio, or even the internet, a pub, a racecourse, and a cemetery were the immediate civic priorities of Australia’s regional towns. Until they were large and prosperous enough to erect their own venues for entertainment, the travelling show solved an essential economic problem: how to profitably deliver professional entertainment to the greatest number of people.

Australia’s earliest example of a travelling show was Signor Luigi Dalle Case’s Foreign Gymnastic Company, a small circus-like troupe which serendipitously arrived in Sydney in 1841, having travelled from Europe by way of Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town and Mauritius. Dalle Case and his little troupe subsequently visited the inland towns adjacent to Sydney, entertained the military establishment on Norfolk Island, then visited Hobart Town and the interior towns of Van Diemen’s Land, before departing for India. But Dalle Case’s visit did not immediately launch of a colonial travelling show industry. The colonies were still primarily penal settlements, the free population was small, the gold rushes were a decade away.

In the years leading up to the great Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, the Australian colonies were already one of the most urbanised societies in the world, some 40% of the population to be found in Sydney, Hobart Town, Adelaide and several port settlements. The rest of the population was scattered throughout the bush where travelling and living conditions were basic and lawlessness prevailed. As the controversial Scottish Presbyterian minister, John Dunmore Lang, observed during his tour of the interior townships of New South Wales in 1834: The three never-failing accompaniments of advancing civilisation are a racecourse, a public house and a gaol.

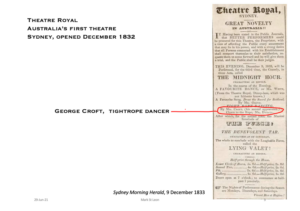

The expansion of the free population inevitably led to demands for the provision of entertainment. Although it was well understood that popular culture and recreations could transform the shared values of the lower orders into contempt for the prevailing order, a theatre was licensed to open in the saloon of the Royal Hotel in George Street, Sydney, December 1832. The following December, a ropewalker, George Croft, a former convict, performed on the stage of the Theatre Royal, probably the first public demonstration of any of the circus arts in the Australian colonies. The circus that Croft opened in Moreton Bay (now Brisbane) in 1847 might have qualified as Australia’s first circus but the affair was closed down by the authorities after the clown sung improper songs and Aborigines were admitted. Croft, a baker by profession, returned south and settled with his family in Goulburn where he gave occasional demonstrations of his tightrope skills in the early 1850s. He was sometimes joined by his colonial-born protege, John Quinn. Croft died at Dubbo in 1887.

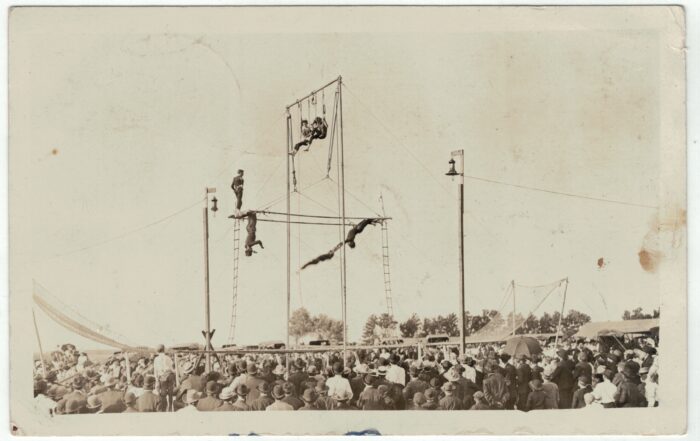

Until the interior was settled by sufficient numbers of people and places of settlement made accessible, few entertainers who ventured beyond Sydney and its outlying townships. Hawkers ventured into the bush knowing that there was a ready market for the supplies they brought from Sydney but professional entertainers rarely ventured out of Sydney but solitary ropewalkers, acrobats and horsemen wandered throughout the bush giving performances wherever a crowd might gather.

The people of the bush found other ways to amuse themselves: reading, picnics, cards, racing, dances and drinking. Some larger towns sponsored their own amateur theatrical societies. This was certainly the case in Goulburn in December 1848, when a party of local people presented a farce entitled The Spectre Bridegroom. This was followed by the performances of an (apparently) Indian juggler named Rammo Sammo, probably after the true Rammo Sammo, an Indian juggler who had long entertained audiences in London. Goulburn’s Rammo Sammo “went through his astounding feats amidst reiterate shouts of admiration from a delighted and entranced audience” but we have no idea of his true identity.

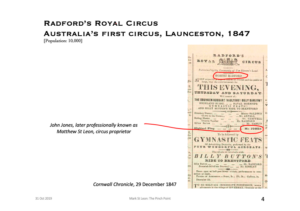

In York Street, Launceston, December 1847, a publican and part-time jockey, Robert Avis Radford, opened Australia’s first successful circus, in the back yard of his drinking house, the Horse & Jockey Inn. Radford’s Royal Circus, as it was called, was presented within a cumbersome demountable timber structure with a canvas roof. The little troupe comprised acrobats, equestrians, ropewalkers, singers and dancers, some with professional circus experience acquired in England. Several of Australia’s early circus performers received their professional training in Radford’s Royal Circus. Two of Radford’s expert equestrians – James Ashton and John Jones – took the idea of circus onto the Australian mainland and, as a result, almost all of the circuses that have travelled Australia ever since can trace their origins, directly, or indirectly, to Radford’s Royal Circus. Thus, Van Diemen’s Land – what we now call Tasmania – may be regarded as the cradle of the Australian circus.

In May 1849, the ‘renowned British horseman’ Ashton, who had already entertained audiences in Launceston and Hobart Town with his ‘bold and fearless style of riding’, brought his little troupe of performers to Port Phillip where they performed in a short-lived circus in Little Bourke Street.

The available evidence shows that Ashton and his little troupe made there way northwards, along a fairly well-defined track that had taken shape since the grasslands of Victoria had been opened up in the 1830s. This track, the Port Phillip Road, as it was called, ‘meandered through the bush … from water stop to water stop’. The track linked Port Phillip – now Melbourne – to Sydney by way of Albury, Yass, Queanbeyan and Goulburn, the approximate route of today’s Hume Highway. The record – specifically the Goulburn Herald – is silent on the matter, it seems fairly certain that Ashton and his little troupe performed in Goulburn as they made their way overland to Sydney during the winter of 1849. Reaching Sydney by early spring, Ashton and his troupe performed on the Haymarket Reserve near today’s Central Station, for years the favoured locality of visiting showmen.

While Ashton made his incursion onto the Australian mainland, his contemporary, John Jones had organised and rehearsed his own equestrian troupe in Hobart Town. In December 1849, the Royal Saxon called into Hobart Town, en route from India to Sydney. Amongst its passengers, the Royal Saxon carried an Irish ropewalker named Edward Hughes who, after travelling and performing in India for several years, was now returning to Sydney. After seeing John Jones and his troupe perform in Hobart Town, Hughes, who went by the professional name of Edward La Rosiere, engaged them, brought them to Sydney where they opened on the stage of the City Theatre in January 1850. This was a small ‘bandbox’ of a theatre in Market Street in the approximate vicinity of today’s State Theatre. From there, La Rosiere, Jones and their troupe visited and entertained the Macquarie towns, west of Sydney, and other small settlements as they travelled overland to Maitland.