By early 1853, about 100 people were starting down the Port Phillip Road from Sydney every day – whether by foot, horse, cart or coach – to reach the new goldfields of Victoria. After entertaining Sydney for several months on his return, Henry Burton and his large circus troupe joined the traffic southwards.

They crossed the Abercrombie River, and performed at every township on the way, taking in the larger places, as Goulburn, Yass, and Albury, where they crossed the Murray in the old-fashioned boats.

The great Australian gold rush unlocked the economic potential of colonies originally conceived as receptacles for England’s felons. Free immigration and pastoral and agricultural expansion began in earnest; interior towns emerged and trade routes expanded. Between 1851 and 1861 the non-Indigenous population of all Australia nearly trebled, growing from some 400,000 to 1.1 million. New arrivals generated a significant shift in the distribution of the population, away from the few urban centres, towards the interior regions. As interior towns emerged, so also did the need to link one to another and to the metropoles. During and after Australia’s great gold rush period of the 1850s, circuses and an ever-expanding variety of other travelling shows began to negotiate variable and volatile economic and travelling conditions. They started to follow – and possibly even define at times – the trade routes that began to emerge to connect the new settlements.

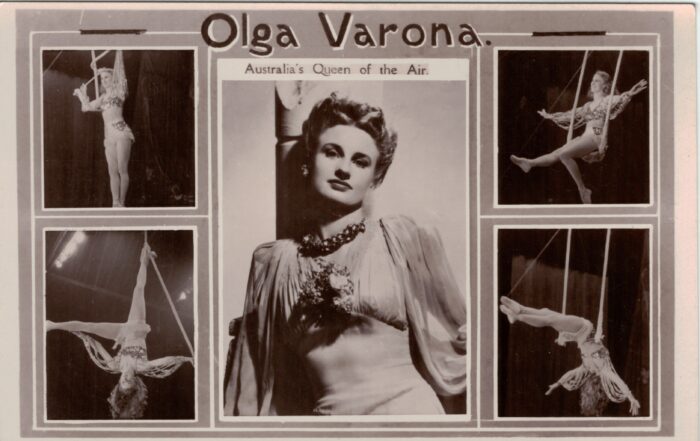

The growing demand for professional live entertainment could only be satisfied by entrepreneurs prepared to organise and conduct shows that travelled, the logical solution to the problem of economically delivering professional entertainment to the isolated communities of town and bush. For more than a century from the great gold rush era, an industry of travelling shows delivered live entertainment to Australians, a potpourri of popular culture that moved between city and town, through the bush and across the outback. These travelling shows catered for every level taste, whether highbrow or lowbrow. There were travelling light-opera companies, vaudeville tent shows, minstrel troupes, magicians, phrenologists, magic lantern shows, bands of musicians, marionette shows, boxing troupes, menageries, carnivals and so on. However, a circus possessed universal appeal. In addition to embracing features of other travelling shows, perennial displays of fine horses and horsemanship were constant sources of human fascination in colonies heavily reliant on horses for transport, labour and recreation. In young colonies with underdeveloped infrastructure, horses were not only essential for transport, trade and agriculture but recreation, racing and circus ring as well.

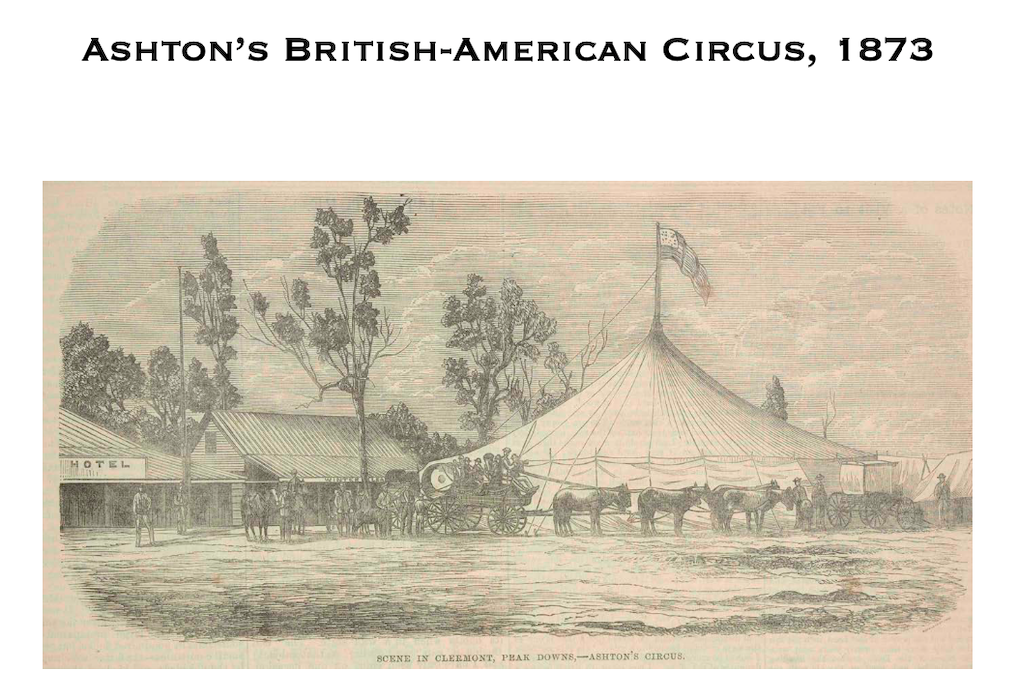

As the great Australian gold rushes of the 1850s quietened down, a handful of colonial circus troupes began to move beyond the relative comfort and security of the coastal settlements and the volatility of the goldfields, to explore and grapple with the challenges of a new frontier. Although location and accessibility might raise the feasibility of visiting a town, a series of towns or a region, the movement of each travelling show through the bush and outback was governed by a range of ‘pull’ and ‘push’ factors. The attraction of local events such as a local agricultural show, a race week or a gold discovery could ‘pull’ a touring circus in one direction while the threat of other events, such as drought, flood, bushfire or competition from a rival company could ‘push’ a company in another. The ability of a showman to successfully negotiate these and other contradictory forces could mean the difference between commercial success and failure. Gradually, by trial and error, the general pattern of travelling show routes on the eastern seaboard of Australia was fairly well-developed by the dawn of the 20th century.

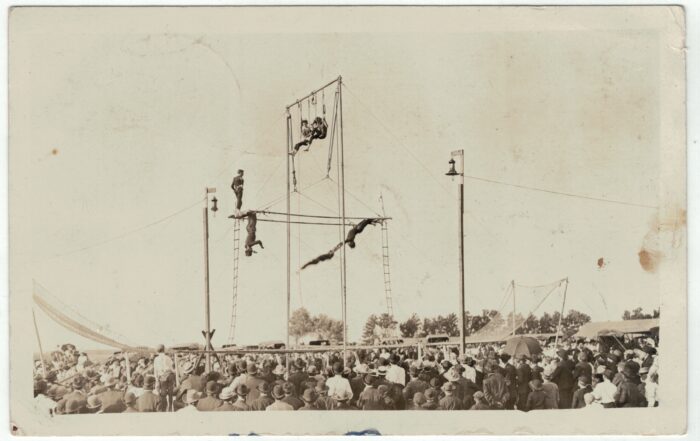

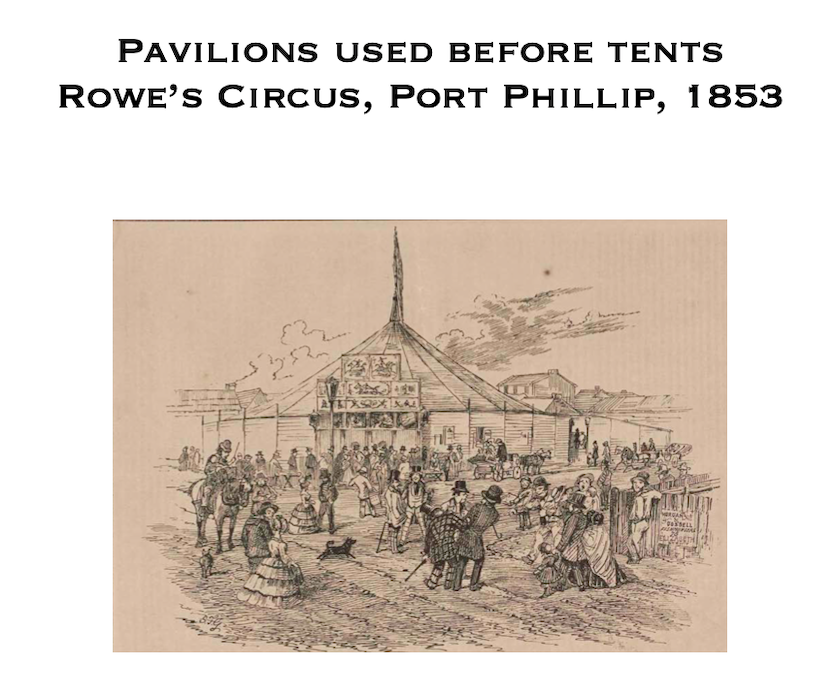

The first peripatetic colonial circuses relied on transportable but cumbersome pavilions or ‘booths’, structures of timber and canvas as seen on the English fairgrounds, erected and dismantled at each location. As circus proprietors on the American frontier had already found, canvas tents were more easily transported, raised and lowered, stored and transported. Also, tents could be quickly configured as the location, weather and anticipated audience numbers required.

By the summer of 1853–54, colonial circus companies began to rely on tents for their accommodation. The early tents were single-pole structures. The centre pole supporting the tent—the ‘king’ pole in circus jargon—was placed in the middle of the ring, necessarily limiting the amount of action that could take place within the arena. As town populations increased, so did the size of audiences. Two pole tents became common. A king pole positioned on each side of the circus ring, not only allowed a larger tent to be erected and accommodate more people but left the ring free for action in any direction.

After Burton’s initial visit to Goulburn in January 1852, Goulburn was regularly visited by one circus or another. This was only natural as not only was the town a major regional centre but it lay on the main traffic route connecting Sydney with the Riverina and Victoria.

By late 1854, Henry Burton had settled on the name of ‘Burton’s National Circus’ for his company, a soubriquet that he retained for the next 20 years. In each town visited, the company entered in procession along the main street, headed by the circus band dispensing fanfares while seated in their custom-made gold and crimson Dragon chariot towed by six cream-coloured horses. Burton followed behind mounted on Sultan, his splendid black charger. Then came the wagons carrying the members of the company and a line of the piebald horses and midget ponies.